One of the most successful World War II rescue operations was initiated by a young woman named Andrée de Jongh.

Andrée was born in 1916 in German-occupied Belgium and was

raised in the shadow of the Great War. Long before she reached adulthood, De Jongh’s

father, a schoolmaster, made certain his daughter was well-versed in Belgium’s wartime

history, its villains and its heroes. Topping the list of the latter were two

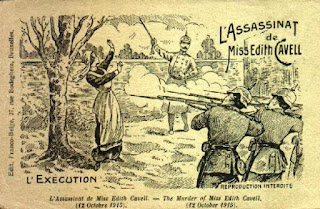

women executed in Brussels

by the Germans: Belgian spy Gabrielle Petit and British nurse Edith Cavell.

Gabrielle Petit commemorative statue

Andrée’s admiration for Cavell was so great that after

becoming a commercial artist, she also trained as a first aid worker. And when

the Nazis invaded and occupied Belgium

in the spring of 1940, Andrée became motivated to emulate Cavell in an

additional way: resistance work, specifically the rescue of Allied servicemen.

French propaganda poster depicting Cavell's execution.

During the First World War, Cavell had facilitated the

escape of Allied servicemen from German-occupied Belgium

and France by hiding them in

her Brussels clinic, then arranging their escape

across the guarded border between Belgium

and the neutral Netherlands.

Andrée had a more difficult task: Belgium was now surrounded on all

sides by German-occupied territory. She, along with her father and several others, decided to commence an enormously

ambitious project: a 1,200 mile escape line that would take trapped servicemen from

Belgium through occupied France, by way of safe houses along the route, and then

across the Pyrenees Mountain range into neutral Spain.

Although the operation’s trial run ended in failure, Andrée refused to quit. Instead, she decided

to ask for British assistance. But when she appeared at the British consulate

in Balboa, Spain,

with three rescued Allied servicemen, the official didn’t believe that this

petite, youthful, neatly-dressed young woman was a resister who had just

traversed the wintery Pyrenees peaks. Rather,

he suspected her of being a German spy. But Andrée eventually won him over

before also gaining the support of MI9, the wartime intelligence organization

tasked with rescuing stranded British servicemen.

While there were many Belgians involved in Andrée’s operation

– eventually termed the Comet Line for its unusual swiftness -- Andrée made 32 round trips

on the line, personally guiding 118 servicemen to freedom. But on January 15,

1943, during her 33rd trip, Andrée

was betrayed into the hands of the Germans. She admitted responsibility for the entire

operation but because of her youthful appearance they didn’t believe her.

However, because she wouldn’t betray anyone else, they sent her to the Ravensbruck

concentration camp.

Photo taken shortly before her arrest.

The Comet Line continued to run in Andrée’s absence, ultimately

rescuing approximately 700 Allied airmen. Andrée managed to survive the war and

received multiple awards from Belgium,

France, Great Britain, and the United States. After

regaining her health, she became a nurse and worked in various leper colonies

in the Belgian Congo and Ethiopia.

When her eyesight began to fail, she returned to Brussels where she died in 2007 at the age of

90.

In Andrée’s

Washington Post obituary, Peter Eisner,

WP

editor and biographer of the Comet Line, claimed it was “the greatest of escape

lines in Europe in numbers of rescues as well as the most sophisticated,

longest operating and most successful."

The value of Andrée’s work, Eisner stated, “went beyond the individuals she

was saving. She gave hope to aircrews in

England before they took off that

there was this angel of mercy working in occupied territory that had a complete

system working to find them. It was a great psychological boost."

Novelist Kristin Hannah has stated that she was inspired to write her best selling novel,

The Nightingale,

after encountering Andrée’s story.

Read the interview here.

Andrée is one of the women featured in my young adult

collective biography (geared for readers 12 years and up),

Women Heroes of World War II: 32 Stories of Espionage, Sabotage, Resistance, and Rescue.

The stories of Andrée's First World War inspirations, Edith Cavell and Gabrielle Petit,

can be found in my second YA collective biography,

Women Heroes of World War I: 16 Remarkable Resisters, Spies, Soldiers, and Medics.