One of the most successful World War II rescue operations was initiated by a young woman named Andrée de Jongh.

Andrée was born in 1916 in German-occupied Belgium Belgium Brussels

Gabrielle Petit commemorative statue

Andrée’s admiration for Cavell was so great that after

becoming a commercial artist, she also trained as a first aid worker. And when

the Nazis invaded and occupied Belgium

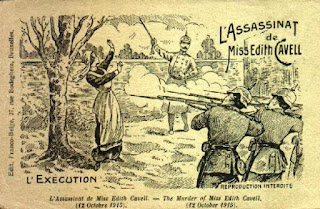

French propaganda poster depicting Cavell's execution.

During the First World War, Cavell had facilitated the

escape of Allied servicemen from German-occupied Belgium

and France by hiding them in

her Brussels clinic, then arranging their escape

across the guarded border between Belgium

and the neutral Netherlands Belgium

Although the operation’s trial run ended in failure, Andrée refused to quit. Instead, she decided

to ask for British assistance. But when she appeared at the British consulate

in Balboa , Spain ,

with three rescued Allied servicemen, the official didn’t believe that this

petite, youthful, neatly-dressed young woman was a resister who had just

traversed the wintery Pyrenees peaks. Rather,

he suspected her of being a German spy. But Andrée eventually won him over

before also gaining the support of MI9, the wartime intelligence organization

tasked with rescuing stranded British servicemen.

While there were many Belgians involved in Andrée’s operation

– eventually termed the Comet Line for its unusual swiftness -- Andrée made 32 round trips

on the line, personally guiding 118 servicemen to freedom. But on January 15,

1943, during her 33rd trip, Andrée

was betrayed into the hands of the Germans. She admitted responsibility for the entire

operation but because of her youthful appearance they didn’t believe her.

However, because she wouldn’t betray anyone else, they sent her to the Ravensbruck

concentration camp.

Photo taken shortly before her arrest.

The Comet Line continued to run in Andrée’s absence, ultimately

rescuing approximately 700 Allied airmen. Andrée managed to survive the war and

received multiple awards from Belgium ,

France , Great Britain , and the United States Ethiopia Brussels

Novelist Kristin Hannah has stated that she was inspired to write her best selling novel, The Nightingale, after encountering Andrée’s story. Read the interview here.

Andrée is one of the women featured in my young adult collective biography (geared for readers 12 years and up), Women Heroes of World War II: 32 Stories of Espionage, Sabotage, Resistance, and Rescue.

The stories of Andrée's First World War inspirations, Edith Cavell and Gabrielle Petit, can be found in my second YA collective biography, Women Heroes of World War I: 16 Remarkable Resisters, Spies, Soldiers, and Medics.

Airey Neave, an agent of MI9, wrote a biography on Andrée

called Little Cyclone: The Girl WhoStarted the Comet Line.

Finally, the book SilentHeroes: Downed Airmen and the French Underground, by Sherri Greene Otis, contains a lengthy, detailed section on

the Comet Line.